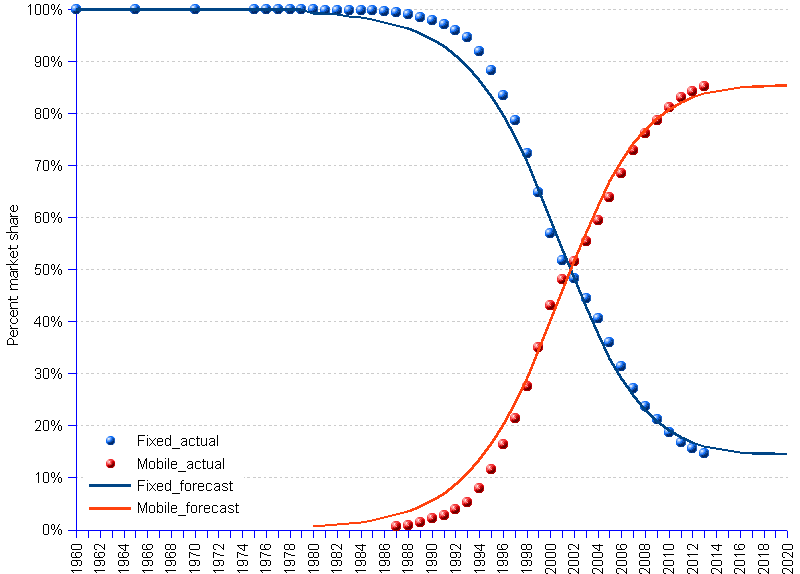

Some problems eventually get solved because we look at the solutions in different ways. Consider the problem faced by communications policymakers in the early 1980s, captured neatly in the phrase :half the world's people have never made a phone call."

That was defined as a supply problem: networks did not exist, not a demand problem (people did not wish to communicate). So the "solution" was hampered by the high cost of fixed networks.

Policymakers struggled with the costs of fixed network infrstructure supply, not realizing that a different approach--namely mobile communications--would arise, and solve the problem. Essentially, we solved a scarcity problem by shifting our choice of solutions.

We avoided the problem of high fixed network cost by switching to more-affordable mobile networks.

source: areppim

More recently, there was a time in the early 2000s when finding a usable Wi-Fi signal was anything but normal. These days, users in developed nations pretty much assumes there will be access at all major venues and most big retail locations, all hotels and most restaurants.

These days, mobile users routinely save money on their mobile data costs by switching over to Wi-Fi at home, at work and elsewhere. Some access providers, including U.S. cable TV operators, actually make that part of their infrastructure strategy.

They emphasize customers using carrier-supplied Wi-Fi instead of using the mobile network whose resources are leased from a mobile operator.

Likewise for messaging, there was a time when a single text message sent from a mobile phone might costs 10 cents. These days, in many markets, use of domestic texting is on a "no additional cost" basis. Multimedia messaging, in fact, has supplanted the majority of text messages, meaning that not even access to a mobile phone is required.

These days, text messaging (Short message service) is supplanted by social app multimedia messaging services.

That has been a pattern in the communications industry. Scarcity is replaced by abundance; new services replace legacy services; services become features; revenue is displaced as legacy service demand dries up.

So though it seems unlikely, the "digitial divide" problem will be solved, and cease to be a "problem."

Scarcity--both real and imagined--drives the prices and perceived value of nearly all products and services. “Lack of” also drives the political agendas of virtually all organizations and entities who promote an agenda.

Those organizations require resources to operate, and resources mean jobs, prestige and power. So what happens when a “problem” is essentially solved? Do organizations disband, or do they find some other “new problem” to work on, thus inviting continued support of the entity?

Almost always, the latter is chosen over the former. So we can virtually predict that, eventually, policy proponents are going to stop talking about the “digital divide” and move on to some other problem related somehow to “inability to buy broadband internet access.”

Already, many point to “digital literacy,” which is a demand issue, not a supply issue, as a substantial remaining problem. In other words, it is not the quality of the available broadband access that limits use, it is the skills of potential users. Faster broadband does not fix that impediment.

But to the extent that generational differences exist, that problem eventually fixes itself. Younger generations are more comfortable with all new technologies than older generations, and as each generation passes, the “lag” evaporates.

There will likely always be “differences” in available speed, latency, reliability or price between remote areas and urban areas, to be sure. Summer fruits and vegetables cost more, and are less fresh, in the winter.

Still, at some point, internet access is going to be good enough that bottlenecks to experience and value will shift elsewhere in the ecosystem and value chain.

Where servers are located; what customer premises gear is needed; how pricing and packaging models are crafted; which indoor transmission platforms are operating and processing speed and power could well determine whether internet apps, services and devices work at all or work properly.

Most are now too young to have encountered it, but back in the 1980s global communications policymakers actually were concerned about how to create “voice access” platforms for most people, as “half the people have never made a phone call.” That might have been true in the 1980s or even 1990s. It no longer is true.

We have “solved” the problem of humans having access to voice communications. We likewise will solve the “digital divide” in a meaningful sense: not defined as absolute parity of speeds, latency or cost per bit, but in the sense of “access” no longer being a barrier to usage.

And that will lead a whole bunch of people and organizations to find some other new problem to solve.

No comments:

Post a Comment