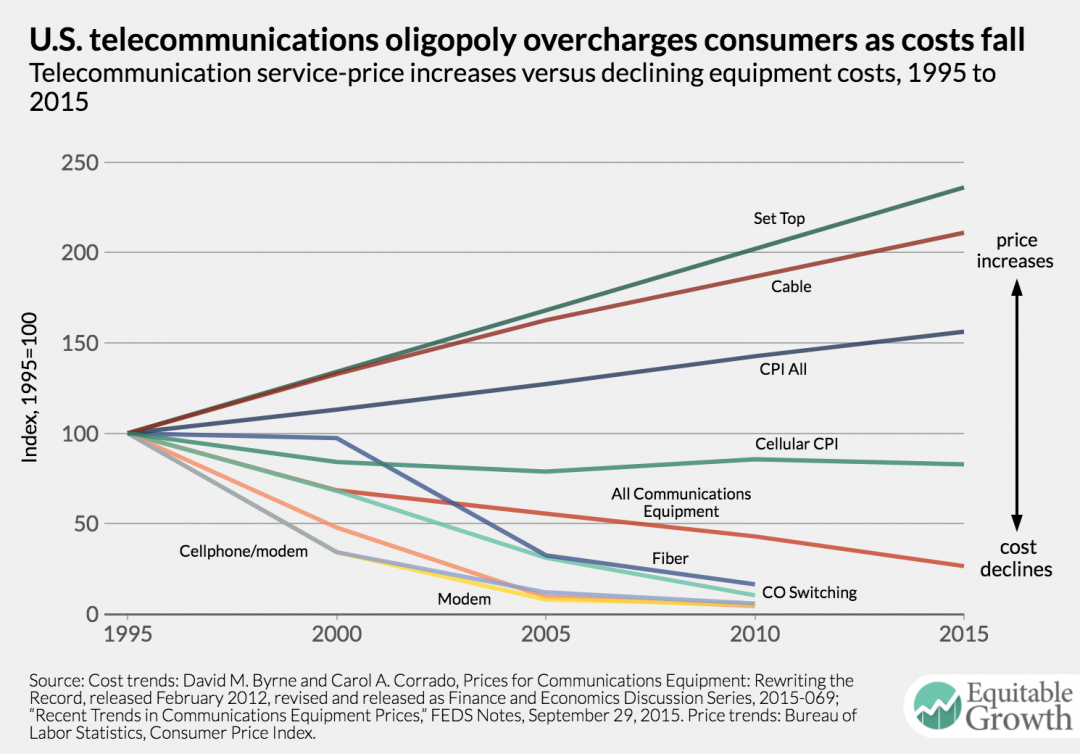

Less competition typically means higher prices for consumers and better profits for producers, and that might be exactly what happens over the next decade as tougher business models cause widespread consolidation of service providers.

In fact, it is hard to find any observers outside of official Sprint and T-Mobile US leadership who believe a merger between those two firms would lead to "more competition" in the market. The whole logic of the merger is to reduce competition and allow higher profits.

Communications regulators also will have to face some new realities about the communications business, namely that competition will be so severe, and business models weakened to such a degree, that market consolidation becomes necessary.

In fact, it is hard to find any observers outside of official Sprint and T-Mobile US leadership who believe a merger between those two firms would lead to "more competition" in the market. The whole logic of the merger is to reduce competition and allow higher profits.

Communications regulators also will have to face some new realities about the communications business, namely that competition will be so severe, and business models weakened to such a degree, that market consolidation becomes necessary.

And that, inevitably, will reduce competition, as such consolidation has reduced competition in the U.S. airline business, and now is starting to reduce competition in the European airline industry.

To be sure, modern communications markets that were monopolies before 1980 have become competitive only for several decades, and have largely remained oligopolies in most markets.

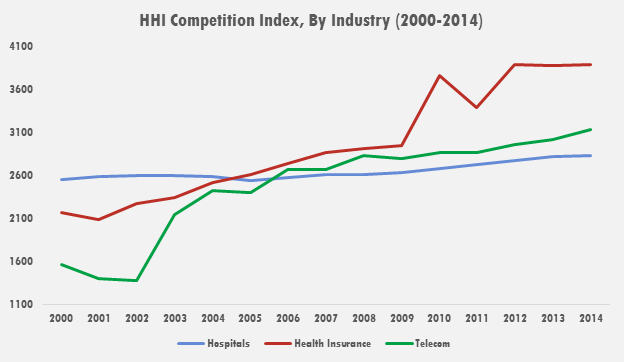

The point is that mobile and telecom have emerged as “highly concentrated” almost everywhere, using the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI), a commonly accepted measure of market

Concentration.

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission in recent years has deemed the U.S mobile market to be highly concentrated, but not as concentrated as some other markets.

On the other hand, many observers, and the FCC itself, would consider the market to be robustly competitive, since the 2011 analyses. Basically, U.S. regulators have considered any markets with HHI scores of more than 2500 to be “highly concentrated.”

When looking at the U.S. market, it can make a difference whether national averages or local areas are analyzed. Some U.S. markets are more concentrated than others.

If the proposed merger between T-Mobile US and Sprint were to occur, it would increase concentration in an already highly concentrated U.S. industry, reducing the number of leading national providers from four to three.

The broader issue, though, is whether such consolidation of markets is inevitable, as the business case becomes more difficult in virtually every market.

Whatever else we might say about coming consolidation in the U.S. communications business, many potential moves will reduce competition and lead to higher consumer prices. That might not be seen as a good thing, but market dynamics seems to be pushing inexorably in that direction.

If such moves happen globally, as many expect, regulators are going to have to change their thinking about how to encourage investment while maintaining competition in core communications markets.

One can argue, at a high level, that two competitors are better than a monopoly, but modestly better for consumers, depending on the actual degree of price and service competition. Likewise, one can argue that three big competitors provide more competition than just two big competitors.

Most would agree that some larger number of competitors--say six to eight--is unsustainable long term, as the market, and present business models, will not support that many major providers, long term. The caveat is that there always seem to be roles for niche providers with small market share. In fact, one can argue that the very smallness of those niches makes them unattractive for the major providers to supply.

To be sure, the telecom industry virtually always has been concentrated for most of the past 150 years. But the level of concentration grew more than 100 percent between 2000 and 2014.

Percent Change in Market Concentration and Regulation

2000-2014

| |

Industry

|

HHI Index

|

Hospitals

|

11%

|

Health Insurance

|

79%

|

Banking

|

100%

|

Telecom

|

101%

|

Airlines

|

16%

|

Auto Industry

|

-34%

|

Energy

|

31%

|

Average Change

|

43%

|

And though many would argue that the U.S. mobile communications market has gotten more competitive over the last several years, despite the concentration, others might argue, looking at other segments of the business (fixed line, cable TV) that concentration has grown.

There are some important caveats. The markets are changing, so “traditional” service providers are losing share to new competitors such as Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime. Traditional internet service providers now are seeing some loss of share to non-traditional and new internet service providers. Long-haul capacity providers are losing share to enterprises that build and operate their own networks.

The point is that market concentration is not the only issue, nor are “high levels” of concentration. Telecommunications always has been a capital-intensive business that can support only a few providers. It is, in other words, an oligopoly when it is not a monopoly.

The big issue for regulators, in the future, is how to regulate, and how much to regulate, when markets have a vastly-different character than at present, with far fewer suppliers.

No comments:

Post a Comment