Over time, in every market, mobile and fixed data costs tend to decline, especially on cost per gigabyte basis, but also typically in absolute terms. Even in the India mobile market, the cost of using mobile data has been dropping since 2014.

Wednesday, May 31, 2017

In-Building Mobile Access: One Size Does Not Fit All

As always seems to be the case, no single “indoor” mobile access approach is “perfect.” In large part, that is because venues vary so much in size. So, as is always the case for any access or in-building distribution network, the solution has to succeed on both cost and capability dimensions.

Looking only at the “in-building” set of solutions (Wi-Fi to small cells), large venues are where the economics are most favorable for multi-carrier, in-building distributed antenna system (DAS) networks, one might argue.

The cost of deploying in-building solutions for mid-sized (perhaps 25,,000 square feet of space up to about 500,000 square feet) is a bigger challenge.

Small businesses represent yet another level of challenge, even if, in the U.S. market, for example, most business sites are in the “small venue” category.

About 92 percent of U.S. businesses, for example, have four or fewer employees. Just six percent have five to 19 employees. So 98 percent of U.S. business sites are “small.”

For the most part, that means commercially-viable in-building mobile access solutions are restricted to a very-small number of large venues and perhaps 550,000 mid-sized locations.

So it makes sense that solutions aimed at indoor mobile access, either single-carrier or multi-carrier, are aimed at a relatively small number of U.S. business locations. Supplier IP Access, for example, believes locations of 100,000 to 500,000 square feet number about 99,000 locations, and include hotels, retail locations, hospitals, schools, high-rise buildings and enterprise headquarters locations.

The tier two venue market segment, called “middleprise” by IP Access, consists of venues from 100,000 to 500,000 square foot locations. There are approximately 99,000 such venues in the United States, IP Access argues.

For small business locations, there arguably is almost no way to affordably supply multi-carrier solutions. Even in many of the mid-market locations, multi-carrier access solutions might face business model challenges.

Tuesday, May 30, 2017

Is Spectrum Really "Scarce?"

The global mobile business, like its predecessor fixed line networks business, was built on scarcity. Monopoly regulation created scarcity by policy decision, allowing only one firm to lawfully provide telecom services in a country. The whole business model therefore was shaped by the deliberate lack of competition.

But there are other forms of scarcity. Even in the competitive era, fixed networks are expensive, capital-intensive undertakings that necessarily limit the number of sustainable providers (some would still say the empirical evidence is that some markets can support only one facilities-based provider; two providers in some markets and possibly three contestants in parts of national markets.

In mobile markets it presently seems possible to support more than one facilities-based provider in every market, though observers disagree about the number of indefinitely-sustainable contestants owning their own facilities.

But mobile network business models also have been built on scarcity of the policy sort, namely by the reliance on licensed rights to spectrum. As virtually anybody would acknowledge, traditionally, such spectrum has been valuable because it has been scarce.

The issue now is whether “scarcity” conditions will continue to define most business models.

And that is open to question.

“Since the 1920s, regulators have assumed that new transmitters will interfere with other uses of the radio spectrum, leading to the ‘doctrine of spectrum scarcity,’” said IEEE Spectrum authors Gregory Staple and Kevin Werbach, over a decade ago.

What would change? Spectrum sharing and, to a lesser extent, new spectrum, it was believed. What is different now, more than a decade later, is that ability to use vast amounts of new spectrum in the millimeter wave region, something most would have thought either impossible or unlikely, in the past.

Even though industry executives and regulators “always” have considered spectrum a scarce resource, that is “not so.” Rights to use spectrum has been the scarce ingredient, a major assumption upon which the business model is built.

Also, the traditional reason for such licensing was to prevent signal interference. But “interference” is a function of device and transmitter performance, not simply the number of simultaneous users. Moore’s Law advances mean that signal processing capabilities are far more sophisticated than was possible in the analog or even earlier digital realms.

There are two huge implications. First, the spectrum portfolios of large cellular phone companies will certainly be devalued. Second, scarcity will not provide a “business moat” around suppliers, as it once did. New competitors will be able to enter the business, simply because the barrier of having “rights to use spectrum” is falling.

The initial signs are that coming spectrum abundance already is having an impact on spectrum prices, which are, in a business model sense, too high at the moment, given rational expectations about future capacity.

One example is the sheer amount of new spectrum that is coming in the millimeter bands, in the 5G era. All spectrum now available for mobile operators to use amounts to about 600 MHz to perhaps 800 MHz of licensed spectrum.

But orders of magnitude more spectrum will be allocated and used in the regions above 3 GHz, as 5G becomes a reality.

In substantial part, the ability to use millimeter wave frequencies explains why abundance is coming. But the ability to share existing spectrum in already-licensed bands, and additional license-exempt spectrum, plus much more sophisticated signal processing and radio technologies, plus use of smaller cells, all will contribute to growing conditions of abundance.

As scarcity was the foundation of every monopoly-era business model, and limited competition has been the reality of the competitive era, radical competition could be the reality of the coming 5G and post-5G eras.

Where business models were based on scarcity, they will be built on abundance, in the future.

Monday, May 29, 2017

Mobile Substitution for Everything?

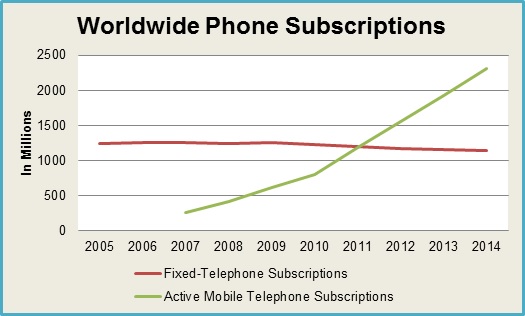

Mobile substitution has become an established fact, in global voice communications markets. That obviously leads to speculation about if, and when, consumers might start substituting mobile for video entertainment, and mobile internet access for fixed access.

At the moment, most of the attention in popular media is about “cord cutting” related to linear video subscriptions. But internet access cord cutting arguably is an equally-big potential issue.

According to Magid’s 2017 Mobile Lifestyle Study, an annual study of 2,500 U.S. consumers that focuses on emerging trends in the mobile market, more than three in ten smartphone owners expressed interest in cancelling their home broadband service in favor of just having 5G. Interest was particularly high among Millennials, exceeding 40 percent.

That is quite a lot higher than the 10 percent of consumers who reported they would consider mobile substitution for internet access found by some other studies. A study by Parks Associates suggests that perhaps 10 percent of U.S. broadband households are “likely to cancel their fixed broadband service” over the next 12 months, and use wireless or mobile data services as a replacement.

Some would argue that coming 5G networks could be a huge catalyst in that regard, dramatically changing the value-price relationship for mobile internet access in ways that make it a more direct substitute for fixed access.

So far, the cost of mobile internet access has been so much higher than the cost of fixed network internet access that mobile substitution has made sense in only limited circumstances.

Where mobile data might cost about $9 to $10 per gigabyte (GB) in the U.S. market, for example, fixed access might cost as little as 15 cents per GB. In other words, mobile data costs about an order of magnitude more, on a per-gigabyte basis, as does fixed network access.

But 5G could be a game changer, allowing mobile operators to credibly match fixed network access speeds and per-GB prices.

Saturday, May 27, 2017

Can Mobile Internet Revenues Replace Lost Voice, Messaging?

One of the “problems” with being early to commercialize any important product is that one reaches the maturity phase of the product sooner than others. That arguably is the case for mobile internet access services, voice and messaging for NTT Docomo and mobile operators in the United Kingdom.

To be clear, many mobile operators, in many countries and regions, are later in the adoption cycle for mobile voice, messaging and mobile internet. They are still seeing revenue and subscription growth.

The point is that every product eventually reaches a peak, and then tends to decline. Some mobile operators simply have more time before that point is reached. Still, maturation will matter.

After mobile subscriptions saturate, after messaging likewise peaks, and when most customers who want mobile internet access already buy it, what comes next?

That is the big question facing developed market operators, and explains why there is such a rush to get 5G into place. Simply put, 5G is the key to internet of things, and IoT is viewed as the key to the next wave of value creation, services and revenues to replace declining legacy access service revenues.

Thursday, May 25, 2017

Little Details, Like Billing, Might Complicate IoT Connection Revenue Models

Even assuming huge new markets for internet of things emerge, and even if huge amounts of new connections revenue are therefore created for mobile and other service providers, there are many pesky business model issues.

Consider only the prosaic matter of how a service provider bills for such a service. In a consumer setting, any stand-alone (by device) method might have billing costs that are a huge percentage of the actual connection revenue generated. In some instances, the cost of rating and sending a bill might exceed the revenue, or cost so much that there is no profit from providing the connection.

If you assume connectivity has to be provided, the issue is how that connectivity is supplied, and “who” pays for it, and how all that gets done on a sustainable basis.

Amazon provides one model, where the appliance supplier pays for connectivity (mobile network) if Wi-Fi is not available, and then uses Wi-Fi as the preferred connection. In that model, connectivity somehow is build into the use of an appliance (does a purchase become a rental?).

Wi-Fi might be an easy choice, as it shifts payment to the owner of the appliance (user pays for the internet access connection). In a few cases perhaps a third party pays (advertising).

That same model could hold for multi-device IoT plans sold by mobile operators, just as they now sell “multiple-device” plans. That has the user paying.

There are exotic possibilities, such as collaboration between a refrigerator manufacturer and one or more large grocers, where an appliance maker works with the retailer and gets a percentage of automated grocery orders. Those might be relatively complex deals for almost anybody but an Amazon.

The point is that moving up the stack might be the best way to ensure that IoT actually produces enough value to create a bigger revenue stream. No service provider is going to want to mess around with billing for a connection that generates less than a dollar a month, at scale, on a stand-alone basis.

Even assuming it is an enterprise or business customer that “buys” the connection service, and billing is in bulk, the service provider might still have to track usage, no matter what the billing cycle.

Cell Geometry for 5G: More, Lots More

Cell geometry has been a big deal ever since mobile operators started using frequencies around 2 GHz, instead of 800 MHz. The basic physics is that as you shrink cell radius by 50 percent, you quadruple the number of cell sites required.

As mobile frequencies climbed into the higher ranges, so did coverage gaps. Where 3G networks might have required one cell site for every 10 kilometers, 4G has tended to require one cell site for every 2 kilometers, said Dr. Arvind Mishra, FTTH Council Asia-Pacific VP.

When 5G comes, it likely will shrink cell coverage to perhaps half a kilometer.

That will simply intensify the trend of proliferating numbers of cell sites. In a 3G environment, mobile operators might have required one cell site to cover 10 square kilometers. For 4G, some 25 cells might be required. In the 5G era, using millimeter wave frequencies, it is possible 400 cells will be required to cover the same area, said Mishra.

5G Really Will Build on 4G

If many of the 5G concepts you hear about are familiar, that is because they are familiar, and are part of the evolution of 4G. Developments such as multiple input multiple output radio arrays developed for 4G will be used for 5G. Carrier aggregation (licensed plus unlicensed) and LTE entirely in unlicensed spectrum will be features of 5G.

In other words, even if 5G eventually will emerge as a distinct generation of mobile networks, it will build on 4G.

"You Can Only Do Pipe So Long"

Some of the language used by speakers at CommunicaAsia 2017 was instructive, especially since, in much of South Asia and Southeast Asia, mobile still is growing pretty fast. But telecom products are products like any other. At some point, given enough time, every potential customer has become a customer, and markets become saturated, ending growth.

“You can only do pipe so long,” said YTL Communications CEO Wing Lee, talking about his firm’s strategy, which does emphasize being the fastest 4G provider in Malaysia but also has created an ecosystem around 4G connectivity, as well as creating its own “Altitude” smartphone that retails for less than US$90, he said.

That sentiment was echoed by Eiichi Sato, NTT East Japan division general manager, talking about the state of fiber to the home in Japan. “It is difficult to further stimulate demand in the saturated broadband market by simply offering high bandwidth,” he said.

The consumer market is “stagnated,” he said. As a result, “new value creation is needed,” said Sato. “Consumer internet seems saturated.”

Johnny Zhang, Huawei Southern Pacific director of fixed broadband business strategy and network, commented that “growth is slowing” in the markets Huawei addresses.

That, in a nutshell, is the reason 5G matters, particularly as a platform for internet of things use cases. In many developed markets, we simply are running out of things to sell customers on high-capacity fixed or mobile networks.

AI is About Insights, Not Robots

Artificial intelligence is an “exponential” technology that will be harnessed in lots of ways, argues futurist Rohit Talwar. Most of those ways will involve application of AI to develop better insights from mountains of raw data.

In fact, the most widespread and useful applications are much more mundane customer service use cases Technicolor, which supplies Wi-Fi management tools to Telstra, uses Amazon’s Alexa service (which uses AI) in its Wi-Fi gateways and access points. Why? To help guide users through Wi-Fi unboxing and set-up.

Forrester Research, for example predicts that “insights-driven” businesses will represent about $1.2 trillion a year in revenue growth by about 2020, essentially representing market share taken from competitors.

There is another potentially-important angle. Over time, virtually all larger companies--and more people within those companies--will be able to use AI to harvest information in a direct way.

While in 2015 only 51 percent of data and analytics decision-makers said that they were able to easily obtain data and analyze it without the help of technologist, Forrester expects this figure to rise to around 66 percent in 2017.

Some observers think that sort of spreading capability also will eventually lead to something we might call “artificial intelligence as a service,” where virtually every business will be able to use AI-driven algorithms to extract business value from data. So eventually, contestants with more data to mine might gain advantage over competitors who have less data to mine, and hence can derive fewer insights.

There might be other analogies. Most of the value of internet of things might well come from the analytics and insights, not the communications function linking sensors with servers.

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

"Indoor Mobile" in a Shared Spectrum Setting

As so often happens, the most interesting conversations happen not in conference sessions, or even in conference hallways, but after hours, in meals or catching up with business associates one has not seen in more than a decade.

So after some time spent reconnecting, the talk turns to the big trends each of us were seeing. Some of the conversation was on business model changes in the mobility space, value creation versus cost cutting and new ways to look at value. Without suggesting we had any fully worked out thoughts on revenue models in the mobility space, much of what we talked about was where value creation could change in terms of “outdoor and mobile” access compared to “relatively stationary and indoor” access.

To some extent, you already see that, with Wi-Fi for indoor and mobile networks for outdoors. But shared spectrum (Citizens Band Radio Service) maybe is the first commercial indication of possibly-bigger changes to come.

On the model of Boingo, perhaps, one can envision the emergence of new specialist roles for indoor mobile infrastructure and service providers. While not implying that this alters in a fundamental way the market dynamics of the mobility business, there are strategy and capex implications, wholesale opportunities, as well as more chances of realistic mobile substitution for internet access with scale.

So the question is how big a business "indoor mobile" might become.

Why 5G is Coming So Fast

In much of Southeast Asia, the notion that mobile internet access is “mature” is laughable. In fact, in many markets, the sheer volume of subscriptions still is growing, and therefore voice and text messaging revenues still are climbing.

So it has been a bit startling to argue that, despite those present favorable trends, growth in all those areas (mobile subscriptions, voice revenues, text messaging revenues, mobile internet access) eventually will reach saturation, then decline. Those discussions have come in the context of talking about 5G.

A longish story made very short, the reason 5G is coming so fast in the developing markets is that we simply have run out of ways to make more money on 4G. Specifically, 5G means support for internet of things, which means new services and connections for machines, not people.

People seemed to get the argument that, eventually, you run out of potential customers. At some point, every human who wants to buy and use all manner of mobile and communication services, already does so. And as one might inelegantly put it, consumers are not going to spend 10 times more on what service providers have to sell, in the connectivity services area.

There’s no other way to explain why 5G now is coming so fast. People seemed to get that.

Indoor Wi-Fi Coverage and IoT

Indoor coverage remains a significant problem for mobile and Wi-Fi networks, problems that small cells and other solutions are expected to help remedy. According to data generated by Technicolor, perhaps 60 percent of reported Wi-Fi problems are remedied by moving either an access point or a base station.

That might also imply that up to 60 percent of Wi-Fi problems can be solved by using a small cell remedy. Possibly 35 percent of Wi-Fi problems, though, seem to created on signal interference issues or congestion on the actual Wi-Fi channel being used by a customer.

That problem can be fixed if the access provider has a way of adjusting channels automatically, without some action by the user. In addition to higher satisfaction, that also should lead to fewer inbound contacts to customer service personnel, which also then should lower customer service costs and churn.

Greater use of internet of things will increase the importance of indoor coverage. In the past, a customer with a reception problem (mobile or Wi-Fi) could just move locations. That will not be the case for all internet of things devices, which might well be stationary.

The “move closer to the window” or “go outside” approach will not work, in such cases.

Will New Narrowband Services Drive Most Incremental Revenue Growth?

Truly revolutionary changes do not happen all that often in the communications business. But they do happen. Voice once drove the revenue model and use cases. Then text messaging drove growth, followed now by broadband internet access, mobile and fixed.

Business models once assumed monopoly supply; now we assume competition.

Services were sold mostly to support human-related requirements, though services directly aimed at machines have grown.

In the emerging era, we might find that much or most of the actual growth of use cases and revenue comes from services for machines that only require narrowband connections.

For virtually all of the last 30 years, networking technologists and business leaders in the information and communications industries have rightly assumed that “faster speeds” and therefore higher data throughput rates were virtually directly related to financial outcomes.

In other words, the ability to send data faster increased the value of communication networks, made more use cases viable, and therefore drove revenues for suppliers of networking platforms, service providers.

So it is noteworthy that in the next phase of value creation and industry development, narrowband platforms might drive the next big wave of revenue.

That could well be the case if internet of things use cases develop as widely as expected. Look at the direction of standards extensions of Long Term Evolution, for example. Standards bodies that traditionally have worked to wring more performance out of networks now are working to create networks that feature less bandwidth.

Cat-1 for LTE networks tops out at 10 Mbps in the downlink, 5 Mbps in the uplink. But Cat-M1, the next development, will feature just 1 Mbps peak data rates, upstream or downstream. The Cat-NB1 standard will support just 20 kbps in the downlink and 60 kbps in the uplink.

Those developments are related directly to the expected use cases for sensor reporting, which quite often entails only uploading small amounts of data, but also communications cost and battery life.

The shift to perceived business use of narrowband platforms is a huge shift. All the direction has been towards broadband (faster speeds, more data throughput) in communications, for decades.

So 5G will be the first networking era in quite some time where, despite use cases for higher speeds, the real use case and revenue upside will come from narrowband platforms.

Sunday, May 21, 2017

One Measure of How Much New Price Competition Has Hit the U.S. Mobile Market

Nearly half of the decline in core consumer price index inflation in 2017 can be traced to a single item: mobile services, according to Paul Ashworth, Capital Economics chief economist.

Mobile service plan prices dropped seven percent in March 2017 and fell an additional 1.7 percent in April 2017, according to Labor Department data.

From April 2016, mobile service prices were down 12.9 percent the largest decline in 16 years.

Core inflation—prices excluding the volatile categories of food and energy—rose just 1.9 percent in April 2017 from a year earlier, decelerating from 2.3 percent growth in January 2017, as measured by the U.S. Labor Department’s consumer-price index.

When in your career and life have you ever heard anyone assert that lower mobile service prices accounted for half the change of the consumer price index?

Friday, May 19, 2017

Europe Mobile Operators Want 5G Framework that Encourages Investment

A group of leading European mobile operators have responded to a European Commission inquiry on 5G policy by arguing a lighter regulatory touch, and a focus on incentives for investment are required.

The group of mobile operators, supported by some big industry vertical partners, also argues that “sufficient spectrum, licensed in time and at reasonable prices” also is required. None of that would come as a surprise.

The industry wants “fewer and simpler rules” where it comes to wholesale access to key infrastructure that is not replicable through competitive investment. In other words, as often is the case, retailers want wholesale access to be simple and fast.

Mobile operators also want better investment return frameworks, in contrast to prior EC policies that emphasized competition (to produce lower prices and other consumer benefits).

When a Market Grows At the Margin, Marginal Changes Can be Big

In any market where growth or decline is at the margin, as telecom revenue tends to be, relatively small changes can change the trajectory of growth.

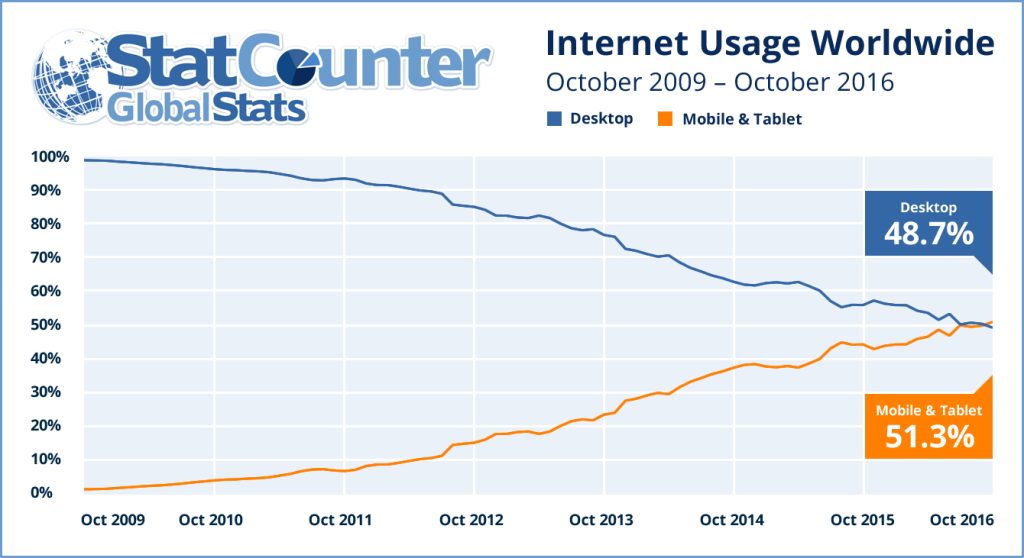

Paradoxically, for example, some studies show both growing use of internet access, and declining purchasing of home internet access services. One plausible explanation is that a growing percentage of customers choose to rely solely on mobile internet access.

|

| source: StatCounter |

It appears that virtually all the growth in broadband usage in Tennessee, for example, since about 2013, has come either from mobile or some other method of gaining access, based on a reported decline in home internet access purchasing since 2013.

There was a seven percent net gain in internet usage between 2013 and 2014, even as fixed network access dropped two percent. That suggests consumers are opting increasingly to use the internet significantly or primarily on their mobiles.

In the U.S. market, about 12 percent of all internet users relied solely on mobile only for internet access.

Fixed network adoption in Tennessee seems to have peaked about 2013, even as internet access adoption climbed to 81 percent.

That trend, reported in other earlier studies, suggests that mobile internet now is what is driving incremental subscription growth.

The point is that all things related to use of the internet, its apps and devices change with time. It almost does not make sense to distinguish between "broadband" access and ""internet access." It no longer makes sense to ignore the huge amount of internet access that happens in the mobile domain.

Nor, where it comes to measuring "broadband" or "internet access" progress, can be ignore the role played by mobile internet access.

The point is that all things related to use of the internet, its apps and devices change with time. It almost does not make sense to distinguish between "broadband" access and ""internet access." It no longer makes sense to ignore the huge amount of internet access that happens in the mobile domain.

Nor, where it comes to measuring "broadband" or "internet access" progress, can be ignore the role played by mobile internet access.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Is Sora an "iPhone Moment?"

Sora is OpenAI’s new cutting-edge and possibly disruptive AI model that can generate realistic videos based on textual descriptions. Perhap...

-

NTT researchers recently demonstrated ability to transmit 100 Gbps at 300 GHz frequencies, far beyond the ranges we have used for freespa...

-

Rich Communications Services was intended to be the multimedia successor to SMS (short message service). It still seems likely to do so, tho...

-

The general consensus now seems to be that 5G will be adopted about as fast as 4G. That said, one might argue that adoption curves for 2G an...