"Speeds and feeds" historically have lost their differentiating power. That clearly has been true for personal computers, and should be the case for cloud computing, edge computing and internet access generally.

In the connectivity business, the "mobile substitution" trend has occurred in phases, and affected a wider range of products over time.

Mobile voice supplanted fixed voice as the preferred consumer use case. Mobile messaging displaced voice. Mobile social media displaced fixed modes. Mobile turn-by-turn navigation displaced dedicated GPS devices and maps.

Mobile phones displaced watches, cameras, music players and flashlights. Mobile entertainment video is encroaching on fixed modes of viewing (TV sets, PC or tablet screens).

Mobile internet access, which began to find niches in the 3G era, found many more use cases in the 4G era (both for home broadband replacement and on-the-go access). In developing regions, mobile internet access is the preferred form of access.

In the 5G era, we will see a big test of fixed wireless and mobile wireless as a substitute for fixed network access in a wider range of settings. No later than 6G, we might routinely be using mobile access as a substitute for home broadband. The key enabling trends are higher routine speeds and some shifts of pricing plans and consumer behavior.

We can assume every consumer will want their own mobile device. That also means per-device charges. Consider the price of using mobility as a necessary sunk cost. At some point, the issue will become "do we still need to buy home broadband if every single supported device has fast-enough speeds and performance?"

It will be the same question people asked themselves when pondering the purchase of home phone service. When every adult or teen in the family already has their own phone, what is the value of a home phone?

To be sure, fixed internet speeds are going to be mind-gobbling in coming decades.

How fast will the headline speed be in most countries by 2050? Terabits per second is the logical conclusion. Though the average or typical consumer does not buy the “fastest possible” tier of service, the steady growth of headline tier speed since the time of dial-up access is quite linear.

And the growth trend--50 percent per year speed increases--known as Nielsen’s Law--has operated since the days of dial-up internet access. Even if the “typical” consumer buys speeds an order of magnitude less than the headline speed, that still suggests the typical consumer--at a time when the fastest-possible speed is 100 Gbps to 1,000 Gbps--still will be buying service operating at speeds not less than 1 Gbps to 10 Gbps.

Though typical internet access speeds in Europe and other regions at the moment are not yet routinely in the 300-Mbps range, gigabit per second speeds eventually will be the norm, globally, as crazy as that might seem, by perhaps 2050.

The reason is simply that the historical growth of retail internet bandwidth suggests that will happen. Over any decade period, internet speeds have grown 57 times. Since 2050 is three decades off, headline speeds of tens to hundreds of terabits per second are easy to predict.

source: FuturistSpeaker

Some will argue that Nielsen’s Law cannot continue indefinitely, as most would agree Moore’s Law cannot continue unchanged, either. Even with some significant tapering of the rate of progress, the point is that headline speeds in the hundreds of gigabits per second still are feasible by 2050. And if the typical buyer still prefers services an order of magnitude less fast, that still indicates typical speeds of 10 Gbps 30 Gbps or so.

Speeds of a gigabit per second might be the “economy” tier as early as 2030, when headline speed might be 100 Gbps and the typical consumer buys a 10-Gbps service.

source: Nielsen Norman Group

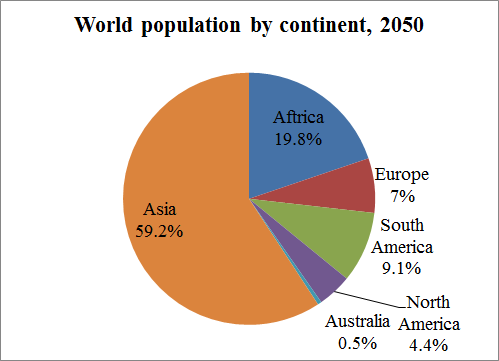

If consumers on every continent purchased service at equivalent rates, in 2050 one would expect Asia to represent nearly 60 percent of demand, Africa nearly 20 percent. Europe would represent seven percent of demand, South America nine percent, North America four percent.

source: Chegg

Most observers would guess Asia will do about that well, while Africa lags. Europe and North America likely will over index, while South America might do about what the population alone would predict.

Though the correlation might be less than one might expect, fiber to home deployment should correlate with terabit take rates in 2050. The wild card is 8G mobile access. As mobile speeds likewise continue to increase, most consumers might prefer wireless access to any fixed connection.

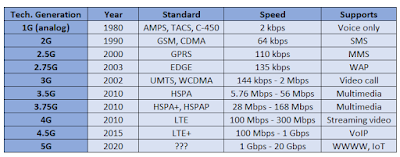

But mobile network speeds will increase at high rates as well. The rule of thumb is an order of magnitude increase every 10 years.

In mobility as in the fixed network, the theoretical headline speed is not matched by mass market commercial experience. Still, the pattern has been that each next-generation mobile network features data speeds an order of magnitude higher than the prior generation.

source: Voyager8

Assume that in its last release, 5G offers a top speed of 20 Gbps. The last iteration of 6G should support 200 Gbps. The last upgrade of 7G should support 2 Tbps. The last version of 8G should run at a top speed of 20 Tbps.

At that point, the whole rationale of fixed network access will have been challenged, in many use cases, by mobility, as early as 6G. By about that point, average mobile speeds might be so high that most users can easily substitute mobile for fixed access.

So among the big strategic questions for fixed network service providers is what to do if and when mobile broadband becomes an effective substitute for fixed network home broadband, as was the case for voice, messaging, social media, most web and app experiences, gaming and so forth.

The fixed network "always" will be necessary for wide area data transport, radio backhaul and enterprise site access. Whether it is so important for access use cases increasingly will be in doubt.

Ultimately, the enduring value of the fixed network is backhaul, enterprise access and WAN transport. Everything else could change.